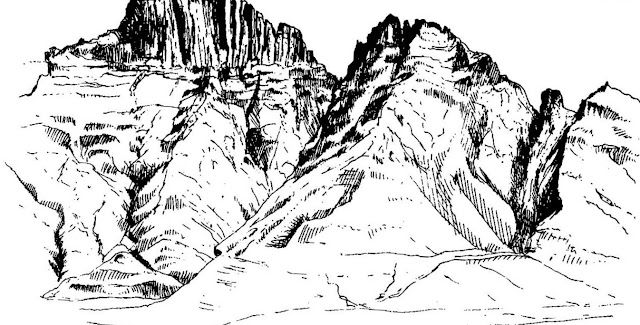

Quathlamba

“A

mass of Spears. Named thus by the Zulu warriors before the white man came.

Today called the Drakensberg, Mountains of the Dragon, a name given by the

Voortrekkers. Evocative names, both equally applicable to South Africa’s

mightiest mountain range with its spear-like peaks – reminiscent of the

saw-toothed spine of a gigantic dragon.”

Panorama April 1966

This blog is

all about the Drakensberg Mountains and its Wilderness area, South Africa. I

have lost my heart and soul to this area and every single time I hike these

mountains, I stand in awe all over again at this magnificent beauty.

“Listen to the streams as they

gurgle from their cradles and you will hear the story of the mountains. You

will hear fascinating tales if only you listen! Lie next to a stream and listen

to the song of the mountains. The smiling faces of the flowers, dancing in the

wind. Venture into the remote valleys or stand on a peak at sunrise or sunset,

after snow has fallen, and you will hear a song that you will never forget -

the Song of the High Mountain". (DA Dodds)

Hiking

adventures, hiking gear reviews, day walks, accommodation, books, articles and

photos, all related to these magnificent mountains will feature here.

Should you

want to accompany me on a hike, or need some information or advice, please make

contact with me. I hope you enjoy the articles.

Please visit

the archive for some more interesting stories, photos and reviews.

Please note that all photos on

this blog are copyright protected. If you would like to obtain

Photos please make contact with

the author, Willem Pelser.

“What have these lonely mountains worth revealing?

More glory and more grief than I can tell;

The earth that wakes one human heart to healing

Can centre both the worlds of Heaven and Hell”

DRAKENSBERG FIRST THE BUSHMEN…….

In Southern

Africa the Bushmen roamed the country long before the black people and

Europeans arrived on the scene. Once it was thought that the Bushmen migrated

from the North ahead of the hordes of black people, but the discovery of

Namibian rock paintings more than 14000 years old by Dr. W E Wendt, a German

archaeologist, in a rock shelter which he called Apollo II, could suggest that

art had its origin in Southern Africa and not Europe, and that The Bushmen did

not migrate from the North but evolved in Southern Africa.

These

Bushmen roamed the plains of the Southern parts of the continent, undisturbed,

leading the life of nomads, hunting wild animals and collecting wild fruits,

berries and bulbs. They seemed able to adapt themselves to almost any

environment.

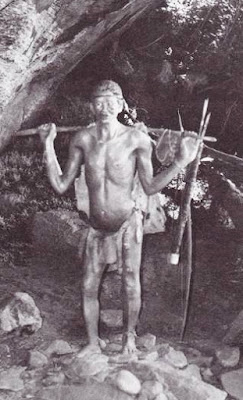

Physically

they were wiry and short of stature, about 1.5 meters high, deep-chested with

small hands and feet compared to the rest of the body. Their faces were

tri-angular in shape with prominent high cheek bones, the eyes wide apart and a

flat nose with a broad ridge. The color of the skin was yellow-brown. They had

a Mongolian appearance and, like Mongolians, the men were beardless. The

females displayed a peculiarity called steatopygia, which was a grotesque

over-development of the buttocks for fat storage, similar to the hump of a

camel.

The men wore very

little clothing. In summer, and on hot days, a tri-angular lion cloth made from

animal skin was their only garment, but when the snow lay thick on the

mountains, they covered themselves with a cloak. The women also wore an apron,

but in addition covered their buttocks with a back skirt. On cold days both men

and women wore a cloak. The seemed to favor a cloak made from Dassie (Hyrax

capensis) fur.

Their hair,

which was of the “peppercorn” type, was usually left uncovered or, according to

19th century ethnologist, GW Stow, was sometimes shaved leaving a

tuft which was anointed with an aromatic preparation.

These Stone

Age hunters loved to decorate their bodies with ochre or clay. On their arms

and legs they wore bracelets and anklets of beads made from ostrich eggshell

and wood. The soles of their feet were protected by sandals constructed from

animal hides. These highly specialized hunters lived and hunted in this

mountain paradise where the vast grasslands supported large herds of antelope

as well as other forms of wild life.

Their homes were the rock shelters found at the base of the

sandstone cliffs. The family unit consisted of one or two related families,

probably depending on the size of the shelter available and the number that the

hunters in the group could feed.

The men

were the hunters and their weapons were bows and arrows. Arrows were made from

reeds with agate, stone or bone tips. Later, when the Bushmen contacted the

black tribes, iron replaced the bone or agate arrowheads. Some of the

arrowheads had barbs. In about 1925, a farmer, Anton Lombard, found a Bushman’s

hunting equipment on a ledge in the “Eland Cave” near the Mhlwazini

River. The equipment consisted of a bow, leather bow case and a quiver

made from wood with leather covers at both ends, containing 22 arrows, two

hunting knives and a small bag containing a resinous substance.

On occasions

the arrows were worn on a headband in a fan-shaped pattern, probably for ready

access. The arrow heads were smeared with a deadly poison, prepared from

extracts of various plants, the venom of snakes, spiders and scorpions.

Opinions regarding the exact ingredients vary but, according to Stow, Amaryllis

disticta, Acokanthera venenata and the milky secretion of the Euphorbia

were the plants commonly used. The rock art author, H Pager, who surveyed the

ecology of the region, is of the opinion that in the Drakensberg it is possible

the genus Urginea, of which there are 3 species, could have been used.

The extract is a potent poison and is used by the Nyika tribe in Tanzania.

Euphorbia

clavarioides is also fairly common in the mountains and would have provided

a perfect additive for the poison. In the event of accidental injury, a readily

available antidote, namely wood ash, which counteracts the Urginea

poison, might have been used, as it is used in the medical practices of the

above-mentioned Nyika tribe.

The Bushmen

had a profound knowledge of the habits of all animals and were experts when it

came to recognizing the tracks of their prey. Having spotted their quarry they

stealthily stalked the animal until they were sufficiently near to enable them to

shoot the deadly, poisonous arrow into the animal. Then they followed it until

it dropped. Many ingenious methods of hunting were also used. One of the 19th

century ethnologists reports that the hunters approached a herd of antelope

wearing the head, horns and skin of a buck, and when close enough the hunter

would pull the bowstring and send the poison arrow into one of them.

A method

of capture used by the Bushmen was to dig deep pits in which sharpened stakes

were placed on the floor and the opening carefully covered with branches, grass

and leaves. These pits were dug close to waterholes or on game trails. Game

fences were constructed from wooden stakes which were erected to direct the

animals which were chased towards the pits. Any creature falling into one of

these traps was impaled immediately.

The women

were the food gatherers and spend their days searching far and wide for the

vegetable part of Bushmen diet. Bulbs, berries, fruit, roots and plants were

collected and carried in bags made from animal skin. Bulbs and roots were dug

out of the ground by means of a digging stick which was a hardwood stick jammed

into a bored stone giving it impulses. The digging stick was also used as a

weapon.

Bushmen were

particularly fond of meat cooked over the open embers of a wood fire and in

particular they favored the meat of the Eland. Another delicacy was the

chrysalis of ants roasted in animal fat. This is called “Bushmen Rice” by other

tribes. Locusts and flying ants were relished but when food was scarce, frogs,

lizards and even snakes were eaten.

Honey was a

great favorite and bee’s nests were regularly raided. Ropes of plaited grass or

animal hides were made to enable the hunters to lower a companion to a nest on

vertical rock faces. According to MW How, who has written a book on the Lesotho

Bushmen, wooden wedges were driven into fissures or cracks in a cliff face in

Lesotho to enable the raider to climb, step-ladder fashion, to the honey. The

nests were marked by the finders and heaven help anyone found stealing the

honey! Honey was also used to prepare potent, intoxicating drink.

A friend

of the hunter was the honey guide, Indicator indicator, a bird which

has a particular liking for beeswax. The Bushmen followed these birds which

would lead them to the nests and in return the bird was given its share of the

find.

In their rock shelters the Bushmen danced and played

their musical instruments. Dancing was an important part of their lives. In the

glow of the fires at night, dressed in animal skins, they mimed the antics of

various animals with amazing accuracy. Their musical instruments were simple.

The bow was used as a string instrument and a sound box was attached as a

resonator. The music was produced by tapping the string with a stick. Flutes of

different lengths were included in the orchestra and the time was kept by drums

made from hollow tree trunks over which animal skins were stretched.

Handclapping accompanied the beating of the drums which echoed through the

valleys late into the night.

THE ROCKS SPEAKS……

The Stone Age artists decorated

their rock shelters with intriguing art – one of South Africa’s greatest

heritages. From these paintings one can learn a tremendous amount about the

artists – how they lived, hunted, their believes and mythology, the clothes

they wore, their weapons, even historical events such as the appearance of the

black man and the European.

Along the

whole length of the Drakensberg Mountains, and hidden in the deep river

valleys, hundreds of rock shelters are to be found. In many of these shelters,

galleries of some of the finest Stone Age art are to be seen. Huge boulders

were also used if a favorable, protected, dry surface provided a suitable

canvas such as the Xeni Rock at the confluence of the Xeni and Umlambonja

rivers in the Cathedral Peak area.

The paints were prepared from iron

oxides, charcoal and gypsum, depending on the color required. These minerals

were ground to a fine powder and mixed with blood and serum. The brushes were

constructed from the tail hairs of certain antelopes and attached to reeds.

Feathers were also used to apply the paint.

A most

valuable contribution to archaeology was made by rock author Harold Pager, who,

with his wife, spent over 2 years living and working in the rock shelters of

Cathedral Peak and Cathkin Forestry Reserves. His book, Ndedema, is the result of

this painstaking work and has become a classic in the field. He chose a

research area of 196 square kilometers which lies between the Umlambonja valley

in the west, the High Berg in the south and the outer krans of the Little Berg

in the east. In this area Pager recorded 12 762 rock paintings and this number

gives some idea of how many may be found in the whole Drakensberg range.

The

greatest concentration of rock art was encountered in the Ndedema Valley in

which 17 painted shelters were recorded and in all 3909 individual paintings

were described in 17 shelters.

The little

yellow painters seem to have favored human beings as their main subjects and

males are more popularly displayed than females. With pictures beautifully

painted on carefully selected sandstone faces the artists managed to produce an

interesting animated effect. Looking at these galleries one can see Bushmen in the

act of hunting, running, shooting, fighting, dancing and raiding. The women are

painted with their collecting bags and digging sticks. They can be recognized

by their pendulous breasts or by the babies carried on their backs.

After human

beings, the antelope was the next most popular subject painted by the nimble

hands of the hunter artists. They loved to paint the Eland, their favorite

antelope. But one can also find almost any animal which roamed the area

depicted on the sandstone faces.

Many visitors

to painted sites have been intrigued by certain large antelope-headed human

figures which have hooves instead of feet. Fine examples of these strange

figures can be seen in the Main Caves at Giant’s Castle, the Sebaaieni Cave at

the head of the Ndedema Gorge, and in Mushroom Hill Shelter near the Cathedral

Peak Hotel as well as in many other sites.

As early as 1928 a

German expedition led by Pro. Leo Frobenius visited the Sebaaieni Cave and its

members were fascinated by these buck-headed men. Later the Abbe’ Breuil, the

great rock art authority of his day, after seeing the work of Frobenius,

described the figures as foreigners from the Mediterranean region, and not as

Bushmen or Negroid. Neil Lee and Bert Woodhouse, co-authors of the book, Art

on the Rocks of Southern Africa, interpret the antelope heads of the

creatures as being hunting disguises or items of fashionable clothing and

reject the idea that mythical creatures might have been depicted. Harald Pager,

however, calls these extraordinary figures “mythical antelope men”

and points out that they are unusually large and elaborately dressed and

decorated. He says that their hooves could have been neither a useful hunting

disguise nor comfortable footwear. It is more likely, he argues, that they are

figures which have undergone some form of magical transformation.

Many other

bizarre mythological creatures are to be found in the mountains. Some female

figures have long, pointed headgear, winglike arms and hooved feet like the

antelope men. Wilcox, in his book, Rock Paintings of the Drakensberg,

surmises that they perhaps represent the Mantis of Bushmen mythology in one of

its guises.

Neil Lee and Bert

Woodhouse first investigated and described another mythical creature, a winged

antelope which they called the “flying buck”. Harold Pager calls the

same figures “alites” which simply means “flying creatures”, and

this day they all are since all have some form of wings, or, when depicted in

humanoid form, hold their arms in wing-like posture.

All 3

rock art authors come to the conclusion that these “alites” represent the

spirits of the dead. Some of them are indeed depicted in scenes of death and

one gains the impression that here the spirits leaving the body will now travel

to the stars, which the Bushmen regarded as the glowing embers in the heavenly

campfires of the departed.

Much controversy

has arisen regarding the age of these paintings. The oldest are usually

monochromes and bio-chromes. Later polychromes as well as shaded polychromes

appeared until their height of perfection was achieved when the artists changed

from the lateral view of their subjects to the foreshortened perspective,

giving another dimension to the composition. The age of certain paintings which

depict blacks, domestic animals or Europeans in military uniforms firing guns,

are fairly obvious since it is well known when these people arrived in the

Drakensberg and the kind of livestock the possessed. Samples of paint collected

by Pager and dated by the paper chromatography method revealed that the oldest

paintings in the area dated back to A.D. 970-1370 and the most recent A.D.

1720-1820.

The life of these

Stone Age men and women must have been one of peace and happiness in a

beautiful land where food and water were plentiful. Their needs were few but

their pleasures were many. In their rock shelters they played their musical

instruments while some of them mimed the antics of the animals painted on the

walls of the shelter and as they danced so their gigantic shadows moved across

the faces of the rocks.

But far

away black men, almost as big as the shadows cast on the wall, were

approaching. Following them, the first white men, called Voortrekkers and Settlers.

(Then

modern man arrived and promptly started vandalizing the paintings!)

Little did

the Bushmen realize that it would not be long before they would have to

disappear – back into the mists whence they had come. Also, that the white

people would treat them as vermin and wipe the Bushmen off the face of the

earth.

THE FIRST WHITE MAN…

Still

living in their mountain paradise, where herds of antelope grazed on the vast

grasslands of the Little Berg and the crystal-clear streams and rivers raced

down the gorges and the river valleys on their torturous way to the sea, the

Bushmen roamed the foothills, quite unaware of an event which later led to

their complete extermination, the arrival of the black people and the

Europeans.

The first

intrepid explorer to venture into the vastness of the Drakensberg was Captain

Allen Francis Gardiner, a retired officer of the Royal Navy, who after the

death of his wife decided to dedicate his life to missionary work.

The arrival of the Voortrekkers in then Natal,

and the fact that many of them settled in the foothills of the Drakensberg,

Must have seemed to the Bushmen an act of war. The Voortrekkers and Settlers

shot an poached in areas that the Bushmen had for years regarded as their

preserve. So they retaliated by stealing cattle and horses. Whether this was,

in fact, a means of getting their own back or simply a means feeding their

people as the game gradually became scarce, is not really known. It is a fact that the Voortrekkers and Settlers was

not discriminate hunters and shot everything on site, whether they need it or

not. They would kill a Giraffe for the tail and leave the rest of the animal to

rot. Between them they annihilated the Drakensberg wildlife and a race of

Bushmen.

Bushmen were no longer people still living

in the Stone Age. They had learnt to ride horses, and iron arrowheads had

replaced the less effective weapons of bone and stone. Because of the early

depredations the Bushmen were regarded as as robbers and thieves and were shot

on sight as if they were animals. Surprise was the greatest asset of the little

hunters who would choose a moonlit night or even an overcast day when

visibility was limited, and swoop down from the mountains, taking away whatever

cattle or horses they could find. Stealthily they herded the animals, using

their intimate knowledge of the valleys and passes. When the terrain became

very steep they smeared cattle dung ahead of the animals, which would persuade

the captive animals that other cattle had passed that way before them. By the

time that the farmer had realised his loss the raiders had a day’s start.

Irrate farmers immediately

formed commandos and followed the spoor, ready to shoot these robbers. A common

practise of the Bushmen was to kill the cattle by stabbing when the pursuers

were too close, in the hope that this would deter them, but this only made the

farmers more determined than ever to exterminate the Bushmen.

The Bushmen were eventually exterminated

like vermin. No mercy was given to man, women or child, whether robber or not,

and they where normally shot on sight.

So

the Bushmen disappeared...

The End.

Safe Hiking.

The End.

The End.

Willem

Pelser – The Mountain Man

References and Acknowledgements

Extraxt from the

book - “A Cradle of Rivers, The Natal Drakensberg” David A Dodds

Black & White

Photos - “A Cradle of Rivers, The Natal

Drakensberg” David A Dodds

Colored Photos – Bushmen

Paintings – Willem Pelser

Compiled by - W Pelser – May 2015