“IT HAD TO DO WITH HOW IT FELT TO BE IN THE WILD. THE EXPERIENCE WAS POWERFUL AND FUNDAMENTAL, AND AS LONG AS THE WILD EXIST IT WILL ALWAYS FEEL THIS WAY.”

UNKNOWN

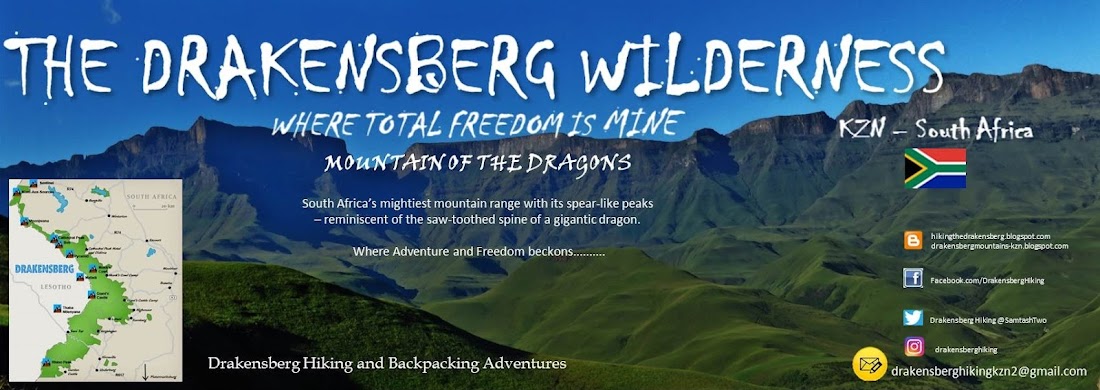

THE DRAKENSBERG

The highest point on the Drakensberg is the incongruously named Ntaba Ntlenyane (nice little mountain), which reaches a height of 3483 m. The whole summit of the basalt island is a jumble of spongy, water-soaked bogs, complex, zigzagging valleys, springs, waterfalls, streams, mist, snow and clouds, all inextricably mixed into a gigantic scenic symphony perfectly described by the greetings exchanged by the Sotho horsemen when they meet one another on the bridle paths which seem to reach almost to the stars: ‘Khotso’ (peace); and ‘Pula’ (rain).

The most spectacular length of the Drakensberg looks down on KZN, Griqualand East and the north-eastern portion of the Cape. For 350 km the Drakensberg presents a high wall of basalt precipices. There are no easy ways over this mass of rock. The few passes are steep, zigzag routes following water-courses. Bridle paths, wilderness trails and tracks follow the contours along the lower slopes, but it takes a mountaineer to find a way to the summit of most of the peaks. In some areas mountain hotels and holiday resorts have been established. Other areas remain completely wild and difficult of access, and demand no little endurance from those with the energy to explore them.

Snow can fall along the Drakensberg in any month of the year, but winter usually sees the heaviest falls. The summer months are marked by some of the noisiest and most spectacular thunderstorms occurring anywhere on earth. From November to May these violent storms break in two days out of three.

Clouds start to close in for the brawl at about 11 a.m. Preliminaries commence at about 1 p.m. with a few bangs and buffets. By 2 p.m. there is a general uproar. To a hiker caught in such a storm is something like trying to shelter in a box of fireworks after somebody else has thrown in a match. Tremendous flashes of lightning seem to tear the sky to pieces. Thunder rumbles, explodes and echoes in an incessant uproar. Rain streaks down at over 50 km an hour, usually turning into hail at some stage, with lumps the size of pigeon’s eggs.

Even more abruptly than they started, these mountain thunderstorms end. The clouds suddenly lift, there is a real flaming sunset and by evening all the stars are out, quite dazzling in the well-washed, pollution-free sky. Storms of longer duration, accompanied by days of clammy mist, also set in at times and bring an average rainfall of 2000 mm, the water soaking into the basalt and then oozing out to feed the rivers.

The vegetation on the slopes, a thick covering of grass and a few shrubs, is sufficient hardy to be able to shrug off these storms – not, however, without many scars. Slopes with a southern aspect – the coldest slopes – are particularly marked by such storm scars. Bare, crescent-shaped terraces pattern the slopes in the thousands. Each of these neat little terraces is about 1 m wide and up to 10 m in length. They appear to be caused mainly by melted water from snow and frost. This icy water saturates the soil, causing it to sag and form these strange-looking scars, rather reminiscent of the incisions made on the faces of certain primitive tribespeople.

The north-eastern end of the basalt ‘island’ is fittingly marked by an outstanding, fang-shaped peak known as the Sentinel. It is 3165 m high and a dominant landmark, visible from KZN and the Orange Free State. Behind it lies a high, boggy plateau overlooked by a gently rising height known as Mont-aux-Sources (the mountain of springs), around whose slopes dozens of springs bubble up and combine their clear waters to form several major rivers in South Africa flowing east and west.

To the east, the plateau falls away in some of the most majestic precipes of the whole Drakensberg.

We as hikers, explorers, and

adventurers have the absolute duty to respect and protect our Wildernesses.

Nobody else will do it for us. Take ownership!

The End.

Safe Hiking.